Early Modern Studies

Theatre History

Theatre History, Attribution Studies, and the Question of Evidence

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023; https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009227391

Full text available for purchase here

Over the past decade, attribution scholars have come to a consensus that Shakespeare wrote some of the additions printed in the 1602 quarto of Kyd’s Spanish Tragedy. This new development in textual studies has far-reaching consequences for established theatre-historical narratives. Accounting for Shakespeare’s involvement in The Spanish Tragedy requires us to rethink the history of two major theatre companies, the Admiral’s and the Chamberlain’s Men, and to reread much of the documentary record of late Elizabethan theatre. Modelling what a theatre-historical response to new attributionist arguments might look like, the author offers an in-depth reinterpretation of Philip Henslowe’s records of new plays, develops a novel account of how theatre companies copied and adapted plays in one another’s repertories (including a reconsideration of the “Ur-Hamlet” and the two Shrew plays), and reconstructs an early modern cluster of Hieronimo plays that also allows us to reimagine Ben Jonson’s career as an actor.

The Jacobean King’s Men: A Reconsideration

The Review of English Studies 70 (2019): 231–251; https://doi.org/10.1093/res/hgy131

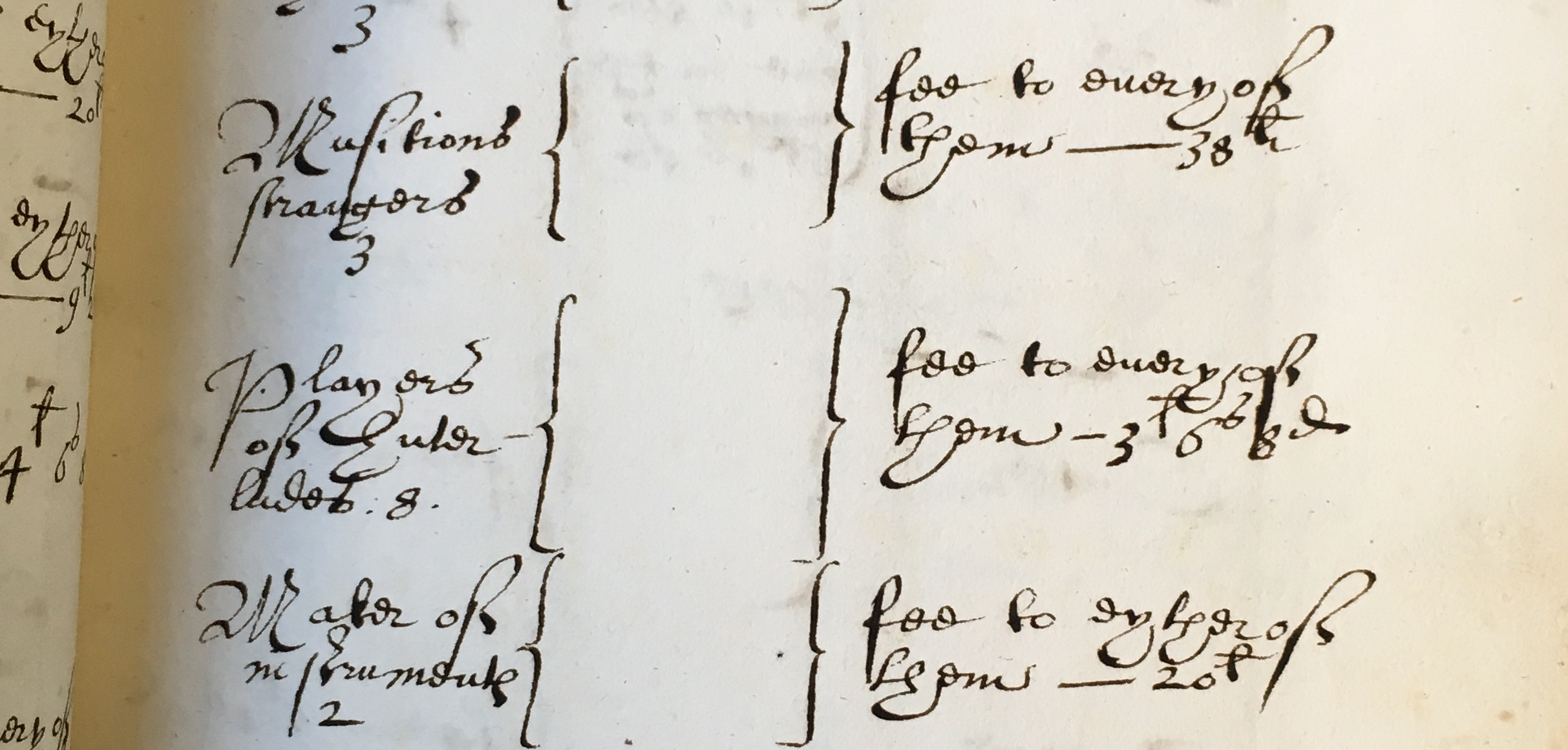

This essay reassesses the history of the King’s Men from 1603 to 1619, in light of new evidence from a 1607 “fee list” discovered in the Beinecke Library and drawing on recently published work on the company’s boy players. It argues that the King’s Men experienced a personnel crisis just as James I became their new patron and responded by developing strategies that would continue to shape the company’s development for decades. The King’s Men not only adopted a policy of training up apprentices to become sharers, but also used the company’s status to poach leading players from other troupes. Finally, the essay makes a case for taking Tudor and Stuart “fee lists” seriously as theatre-historical evidence and argues that players patronized by the monarch may have received an annual set income not just under the early Tudor kings, but under Elizabeth I and James I as well.

A Sharers’ Repertory

Rethinking Theatrical Documents in Shakespeare’s England, ed. Tiffany Stern (London: Arden Shakespeare/Bloomsbury, 2019), 33-51; https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350051379

This chapter argues that to understand how early modern performance schedules took shape and to develop a more comprehensive view of the relationship between repertory and casting, we need to reconsider the importance of “variety.” Its central assertion is that no sharer in a theatre troupe consistently took the largest role in all shows: staging plays was a company effort, and different kinds of plays were associated with different distributions of role sizes and modes of actorly exertion. Generic diversity thus must be analysed not just from the perspectives of marketing and economics, but also as an aspect of company management. In other words, repertories were not just designed to maximize revenues, but also to make the most of a troupe’s talents while avoiding mentally and physically exhausting its sharers. In making this case, the essay draws on a full-text database of early modern drama, used to analyze role sizes and distributions of text across the entire extant repertory.

A Bit of Theatre History: Shakespeare, Female Characters, and Big Leads

A post using the same dataset I also drew on for “A Sharers’ Repertory” to demonstrate how it can be made to reveal patterns, within individual playwright’s oeuvres or for specific companies or as they developed over the decades, in the distribution of roles across a cast of players — how large leads were, how leading roles compared to smaller parts, how male characters compared to female ones, how many identifiable “lead roles” there were in particular plays, or kinds of plays, how distributions of role sizes change over time or between genres, etc. One specific question I address here is the “typical” size of female roles, and how unusual (or not) Shakespeare’s female roles were.

Pastiche or Archetype? The Sam Wanamaker Playhouse and the Project of Theatrical Reconstruction

Shakespeare Survey 71 (2018): 135-46; https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108557177.016

Full text available here (subscription)

In this essay, I am primarily concerned with what we might be able to discover about early modern indoor performance from contemporary theatrical engagements. Broadly, I ask if we can in fact learn anything about playacting 400 years ago by playacting now; more specifically, if we can learn anything about Jacobean indoor playing from the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, the indoor space at London’s Shakespeare’s Globe that opened in 2014.

Post-Curtain Theatre History

The Theatre of Shakespeare’s Time

The Norton Shakespeare: Third Edition, ed. Stephen Greenblatt et al. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2015), 93-118.

This general theatre-historical introduction to the Norton Shakespeare is my attempt to give a picture of the theatrical world Shakespeare knew that avoids presenting questionable hypotheses as facts. In it, I tried as much as possible to leave room for theories that, no matter how persuasively they have been argued within the small world of early modern theatre history, have not yet been sufficiently recognized in broader, non-specialist conversations about early modern theatre. I think — I certainly hope — that it still is the most up-to-date introductory, short account of the history of Elizabethan and early Jacobean theatre that’s currently available in an undergraduate-friendly format. A fuller (freely accessible) summary of its core ideas and theses can be found here.

Fact and Factitiousness: Theatre History and Irresponsible Scholarship

Marlowe in his Moment

Christopher Marlowe in Context, ed. Emily C. Bartels and Emma Smith (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 275-84; https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139060882

Three’s Company: Alternative Histories of London’s Theatres in the 1590s

Shakespeare Survey 65 (2012): 269-89; https://doi.org/10.1017/SSO9781139170000

The Meaning of Success: Stories of 1594 and its Aftermath

Shakespeare Quarterly 61 (2010): 490-525; https://doi.org/10.1093/sq/61.4.490

This essay offers a fresh assessment of what we can and cannot claim to know about the years that have often been described as pivotal to the development of early modern commercial theatre, the mid-1590s. While many influential interpretations, in particular, the alleged duopoly of the Admiral’s and Chamberlain’s Men after 1594 and the abiding dominance of Marlowe and Shakespeare in their repertories, have treated success at court, in print, and on the public stage as equivalent and analogous phenomena, a serious reconsideration of the available data, especially that of Henslowe’s Diary, suggests that these three kinds of popularity should be considered as separate and distinct trajectories. The most successful plays in the Diary were either never published or failed in printed form; Marlowe was popular in print but had practically vanished from the stage by 1596/7; court success is a poor indicator of theatrical success; and there is far more evidence for a continued and increasing diversity of theatrical activity in 1590s London than for a radical restriction of playing to performances by two companies at two officially sanctioned theatres (a proposition for which there is virtually no evidence until 1598). I argue that we need to accept that the Diary and stationers’ publishing decisions represent complex situations and responses, and that abstracting clear and unambiguous rules and conventions from these records is a highly problematic undertaking, likely to confirm rather than challenge prior assumptions and narratives.

Locating the Queen’s Men, 1583-1603: Material Practices and Conditions of Playing

Ed. Helen Ostovich, Holger Schott Syme, and Andrew Griffin (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2009). xiii + 269 pp; https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315592893

Cultural History

(Mis)representing Justice on the Early Modern Stage

Studies in Philology 109 (2012): 63-85; https://doi.org/10.1353/sip.2012.0006

Full text available here (subscription)

Early modern notions of justice tended to be strongly linked to procedural ideals, casting the state rather than the individual as the guarantor of just order, even if specific officials and systems could be identified as falling short of those ideals. In this essay, I trace some early modern perceptions of the proper means of attaining justice and then explore how those means are represented in the period’s drama. As I show, although Renaissance literature’s supposedly “intima[te] . . . engagement with the law” has become a critical staple, there is a striking mismatch between the ways justice was done in early modern England and the judicial processes depicted on stage. I offer a number of explanations for why an accurate portrayal of English judicial procedure may have eluded Shakespeare and his contemporaries and delineate the (not necessarily detrimental) consequences of this misalignment for the dramatic representation of justice.

Theatre and Testimony in Shakespeare’s England: A Culture of Mediation

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012. Paperback March 2014. xiv + 283 pp; https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511997204

Full text available here (subscription)

This book, which was my first monograph, presents a radically new explanation for the theatre’s importance in Shakespeare’s time. It portrays early modern England as a culture of mediation, dominated by transactions in which one person stood in for another, giving voice to absent speakers or bringing past events to life. No art form related more immediately to this culture than the theatre. Arguing against the influential view that the period underwent a crisis of representation, I draw upon extensive archival research in the fields of law, demonology, historiography and science to trace a pervasive conviction that testimony and report, delivered by properly authorised figures, provided access to truth. Through detailed close readings of plays by Ben Jonson and William Shakespeare – in particular Volpone, Richard II, and The Winter’s Tale – and analyses of criminal trial procedures, the book constructs a revisionist account of the nature of representation on the early modern stage.

“While Shakespeare critics debate the merits of text versus performance, page versus stage, Holger Schott Syme’s powerful new study argues for attending the relationship between the two … Syme offers original and unexpected insights into a broad range of dramatic and legal fictions, from comedies and romances to treason trials.” (Lorna Hutson, University of Oxford)

“Syme’s analyses are profoundly revisionary, wonderfully original, even contrarian, and supported by a wealth of careful detail and intelligent and subtle readings. This may be one of those rare books that makes scholars reconsider what has become received wisdom about early modern performance and its means of authorization.” (William N. West, Northwestern University)

“Syme’s book recreates a world view that is in some ways quite alien to us today, a culture where mediated aural performances create a sort of ‘virtual reality’ that serves to produce and transmit the authority of absent powers. Thinking of the virtual realities of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in relation to our own mediated virtual spaces might produce some fascinating further studies. Syme has thus produced an important contribution to our understanding of the theory and practice of both early modern rhetoric and the Shakespearean stage.” (John D. Staines, Shakespeare Quarterly)

Reviewed in CHOICE, Clio, Renaissance Quarterly, Shakespeare Quarterly, Shakespeare Survey, and Studies in English Literature 1500-1900.

The Look of Speech

Textual Cultures 2.2 (2007): 34-60; https://doi.org/10.2979/tex.2007.2.2.34

This essay examines the visual representation of speech, and of the act of speaking, in early modern Europe. It analyses the use of speech-scrolls (rather than modern speech balloons) in theatrical frontispieces and religious paintings as an instance of the transition from oral to literate culture, focusing in particular on conceptual paradoxes arising out of that transition which are largely neglected in standard accounts such as Walter Ong’s. As the essay argues, instead of understanding these images in terms of the shift “from sound to visual space”, they should rather be read as signifying in multiple, and multiply contradictory ways: in the six- teenth century, writing could stand for spoken words, and the written was still frequently figured as a form of speech—in fact, the images discussed in this essay show that the more the visual representation of utterances was made to resemble an actual document (a carefully rendered scroll), the more effectively it could represent vocal utterance. The depiction of speaking as the production of a document does not simply register a complex cultural practice (reading aloud, say), as Ong might argue, but rather constitutes a mimetic strategy arising out of a cul- ture in which “reading continued to be conceived in terms of hearing rather than seeing”.

Becoming Speech: Voicing the Text in Early Modern English Courtrooms and Theatres

Compar(a)ison: An International Journal of Comparative Literature, I/2003 (published 2007): 107-24.

History of the Book

Book/Theatre

Shakespeare/Text: Contemporary Readings in Textual Studies, Editing and Performance, ed. Claire M. L. Bourne (London: Arden Shakespeare/Bloomsbury, 2021), 223-45; https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350128170

Prose and Verse in the 1608 King Lear Quarto: An Alternative Explanation

Thomas Creede, William Barley, and the Venture of Printing Plays

Shakespeare’s Stationers: Studies in Cultural Bibliography, ed. Marta Straznicky (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), 28-46; https://doi.org/10.9783/9780812207385

“But, what euer you do, Buy”: Richard II as Popular Commodity

Richard II: New Critical Essays, ed. Jeremy Lopez (London: Routledge, 2012), 223-44; https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203133668

This chapter analyses the popularity of Richard II from two separate but related angles, first by arguing that far from being moribund in the early 17th century, the genre of the chronicle history play continued to enjoy enduring success; this was true especially of Shakespeare’s history plays. Secondly, the essay examines what specific features of Richard II might have predestined it for success as a book.

Unediting the Margin: Jonson, Marston, and the Theatrical Page

English Literary Renaissance 38 (2008): 142-71; https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6757.2008.00120.x

Full text available here

This essay argues that the publication practices of early modern playwrights like John Marston or Ben Jonson have been widely misunderstood. Through these practices, dramatists did not attempt to distance their works from their theatrical origins, but rather intended to construct an alternative mode of theatricality, thereby reclaiming the visual as a positive force. Through a reconstruction of the relationships between those authors and their printers, and through analyses of their typographic strategies, the essay demonstrates how Jonson in particular made the book his theatre. What emerges is a narrative of Jonson’s publishing activities that avoids the conventional, linear account: the playwright did not consistently seek to escape the theatre, but rather, after an initial attempt to associate his plays with classical drama and humanist scholarship, embarked on a decades-long project of inventing a complex visual code of printed theatricality that culminated in the unfinished 1631 folio, and eventually collapsed, the same year, with the publication of The New Inn.

Editions

The First Folio at 400

Special Issue of Shakespeare Quarterly, forthcoming Winter 2023.

Edward III, by William Shakespeare and Others

The Norton Shakespeare: Third Edition, ed. Stephen Greenblatt et al. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2015).

The Book of Sir Thomas More, by Anthony Munday, Henry Chettle, Thomas Dekker, Thomas Heywood, William Shakespeare and Others

The Norton Shakespeare: Third Edition, ed. Stephen Greenblatt et al. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2015).